This analysis is part of the USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy, which is a partnership between Economic Studies at Brookings and the University of Southern California Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics. The Initiative aims to inform the national health care debate with rigorous, evidence-based analysis leading to practical recommendations using the collaborative strengths of USC and Brookings.

On March 11, 2021, President Biden signed the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (the ARP), a wide-ranging package of health care and economic measures responding to the coronavirus pandemic. The ARP includes a broad expansion of the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) main health insurance subsidy, the premium tax credit (PTC), the first major expansion of the health care reform law since its passage. The provision increases the amount of the PTC for those who are eligible and makes individuals with incomes above 400 percent of the federal poverty line (FPL) eligible for the first time. The expansion is temporary, lasting only through the 2022 plan year.

PTC expansion has profound implications for state health policy, aiding state efforts to make coverage more affordable and accessible. Building on the PTC to make premiums more affordable, using tools like state-based reinsurance programs, supplemental subsidies, and public options, has long been a key focus of state policymakers. A new PTC structure that itself is seen as making premiums broadly affordable is likely to shift the focus to other goals like reducing cost-sharing and expanding outreach efforts to those who are eligible but not enrolled. It could also change the value proposition for broader reforms that draw down federal funding tied to the PTC, like Section 1332 waivers and Basic Health Programs (BHPs).

State responses to the new PTC structure are complicated by uncertainty about its duration and the prospect for additional changes. While many policymakers support making the PTC expansion permanent in subsequent legislation, it is not certain when they might act or if they will succeed. Future legislation or administrative actions may also make additional changes, like addressing the “family glitch,” but the likelihood and timing of such actions are unclear. Amidst this uncertainty, states must continue making decisions about legislation, administrative actions, operational builds, and potential waivers.

States must account for a number of policymaking considerations in light of the PTC expansion and uncertainty about future federal action. A key theme that emerges is that states will benefit from approaches that give them the flexibility to adjust policies year by year as the federal landscape develops.[1]

The ARP’s Broad-Based PTC Expansion

While the PTC as created by the ACA enabled millions of Americans to obtain coverage, many have argued that it is not generous enough, in two key ways. First, the PTC left some consumers who were eligible to receive it owing substantial premiums. For example, a family of four with annual income of $80,000 was eligible for PTC but still needed to pay nearly $7,900 for a benchmark silver plan. Second, PTC eligibility ended in a cliff at 400 percent of FPL, leaving an “unsubsidized” group ineligible for help regardless of the premium they faced.

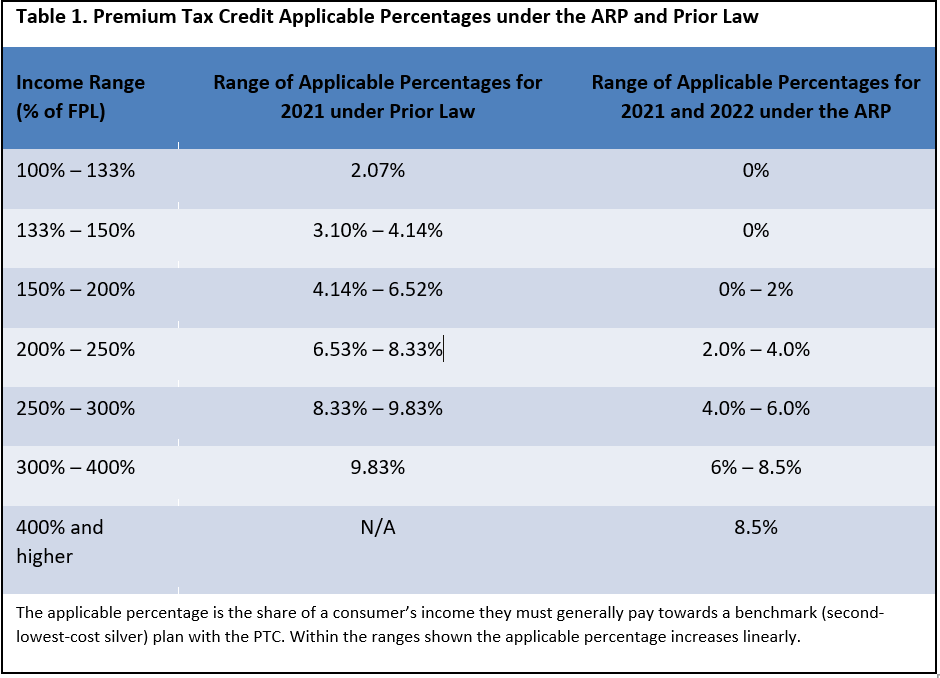

The ARP addresses both concerns for 2021 and 2022. First, it increases the PTC at every income level by reducing the amount consumers are expected to pay as a share of their income toward a benchmark silver plan–the so-called “applicable percentages.” For example, for a family at 150 percent of FPL, the applicable percentage (share of income they are expected to pay) would fall from a little over 4 percent to 0 percent in 2021—providing this family with a fully-paid-for benchmark silver plan. For a family at 300 percent of FPL, the applicable percentage would fall from 9.83 percent to 6 percent. Table 1 shows the full schedule of changes.

Second, the proposal extends the credit to individuals above 400 percent of FPL and applies an applicable percentage of 8.5 percent to that group—compared to no cap today.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) expects this provision (with its two years in effect) to cost $34 billion and reduce net premium for most Marketplace enrollees. It will also increase Marketplace enrollment by 1.7 million people in 2022, of whom 60 percent will have incomes under 400 percent of FPL.

The ARP does not generally address other affordability concerns relating to the ACA’s Marketplace subsidies. It does not generally expand the ACA’s cost-sharing subsidies.[2] It does not modify the rules that preclude PTC eligibility for most people offered employer-sponsored coverage, including the so-called “family glitch” (discussed below). It does not change the rules for undocumented immigrants, who are currently ineligible for the PTC and other public health programs. In short, the ARP temporarily makes premiums more affordable for most consumers while laying the groundwork both for broader and permanent federal improvements and for states to consider approaches to remaining affordability barriers.

State Policymaking Considerations under the PTC Expansion

States have several options to build on federal law to make coverage more affordable and accessible. Some states have already implemented such programs while others are considering them for the first time. A permanent PTC expansion like the one in the ARP would alter considerations and priorities for a broad range of state policies affecting private health insurance. But because the PTC expansion is temporary and there is uncertainty about extension and future action, states face a complex policymaking environment.

State premium subsidies can be targeted to specific populations rather than broadly available. A key state response to concerns that the PTC is inadequate has been state-level subsidies that supplement or “wrap around” the PTC. Four states (Massachusetts, Vermont, California, and New Jersey) currently have these premiums subsidies, a fifth state (New Mexico) has enacted such a subsidy to take effect in 2023, and several others are considering them.[3] A companion SHVS expert perspective highlights state considerations for state-based subsidies. As that piece notes, state premium subsidies may apply broadly to certain income ranges or may be more narrowly targeted to groups ineligible for the PTC or by factors like age.

While it remains in effect, the ARP’s PTC expansion substantially reduces the need for broad-based premium subsidies. The expanded PTC alone is generally more generous than the combination of the pre-ARP PTC and existing state subsidies.[4]

But even with the PTC expanded, state premium subsidies may be a useful tool to target additional assistance. A natural focus would be people who are ineligible for the PTC and other subsidized coverage. The ARP does not address the so-called “family glitch,” which denies the PTC to most people who are eligible for employer coverage, even in some cases where the cost of enrolling in that coverage is very high. Undocumented individuals also continue to be ineligible for subsidized coverage. A state premium subsidy can be targeted to fill these gaps. Colorado’s subsidy legislation sets aside separate funding starting in 2023 to subsidize consumers ineligible for PTC, and other states have considered this approach.

A targeted state premium subsidy could also be used to further reduce net premiums for selected current PTC beneficiaries. For example, New Mexico’s Office of the Superintendent of Insurance has raised the idea of supplementing the ARP’s PTC to provide free coverage to Native Americans.[5] A state premium wrap might also be targeted at young adults with the goal of increasing enrollment among this hard-to-reach and risk-pool-improving group, as under legislation that has passed both legislative chambers in Maryland.

PTC expansion may also cause states to rethink how broad-based premiums subsidies are targeted. For example, with the ARP expected to reduce the cost of New Jersey’s subsidy at relatively low incomes, the state is extending eligibility for its subsidy beyond 600 percent of FPL for the first time.

State cost-sharing subsidies may become a higher priority. The ACA’s cost-sharing reductions (CSRs) lower out-of-pocket costs for eligible consumers, yet like the original PTC are sometimes described as insufficient for some consumers. CSRs are relatively generous between 100 and 200 percent of FPL (providing coverage with a 94 percent or 87 percent actuarial value, or AV) but much less generous between 200 percent and 250 percent of FPL (73 percent AV) and are not offered to consumers with incomes above 250 percent. This leaves some families facing deductibles and other cost-sharing large enough to make their coverage difficult to use—or to discourage them from enrolling altogether. For example, in 2021, a single individual with income of $33,000 is generally ineligible for cost-sharing assistance despite a median individual deductible of nearly $5,000 for federal Marketplace silver plans. A family of three with income of $55,000 is generally ineligible despite average family deductibles in silver plans at least twice as large as individual deductibles.

Like premium affordability, states can improve cost-sharing affordability with state-based subsidies that wrap around federal CSRs. Massachusetts and Vermont have long provided such subsidies alongside their premium subsidies, New Mexico’s new law also provides for both, and other states have considered them. With the PTC expanded, such subsidies are likely to be a higher priority for states. Already, Colorado has decided to shift the focus of its new subsidy in 2022 from premiums to cost-sharing.

Potential for additional PTC changes requires state to remain flexible around state subsidies. While there is support for the ARP’s PTC expansion to be extended, this is by no means certain. Future legislation or administrative actions could also make additional changes, like fixing the family glitch or improving cost-sharing. The potential for future action requires states to remain nimble in their decision-making. States may wish to consider the costs and feasibility of shifting away from broad-based premiums subsidies while also being mindful of later years. Is it feasible to stand up a cost-sharing subsidy in time for 2022? If a state does so but then the PTC expansion expires after 2022, will it be feasible to turn back to a broad-based premium subsidy? If future legislation both extends the PTC expansion and also addresses cost-sharing, how would this impact state policy development and implementation?

States can mitigate the uncertainty by enacting flexible statutes and designing operational systems with an eye toward the possibility of future changes. Some state subsidy statutes clearly define the benefit provided, while others authorize a state Marketplace or insurance department to design the subsidy administratively. This latter approach is more conducive to pivoting in response to ongoing developments. States should also consider how 2022 operational choices affect flexibility for 2023 and later years.

Outreach and facilitated enrollment become even more important. Encouraging those who are PTC-eligible to enroll has become a major state focus in recent years. Even before the ARP’s changes, many uninsured people were eligible for substantial subsidies. Getting them covered improves the wellbeing of state residents and brings federal dollars into the state. Measures to increase take-up are generally inexpensive compared to subsidizing coverage. California and other states have shown success using outreach to expand coverage. Research also shows outreach measures save lives. States have also explored facilitated enrollment to directly connect uninsured consumers to coverage opportunities and simplify the enrollment process. Strategies developed in Maryland have shown promise and are now being emulated in Colorado and have been proposed as part of the governor’s budget in Massachusetts.

With PTC expanded, the case for measures to increase take-up becomes even stronger. More uninsured people (and those in ACA-non-compliant coverage) are now eligible for subsidized coverage, and the subsidies are even larger. Outreach and enrollment efforts are especially attractive amidst uncertainty since they are valuable even if the PTC expansion expires. Outreach also becomes more important to consumers enrolled in the individual market off-Marketplace, as those customers are likely paying full price for coverage very similar to Marketplace coverage for which they could receive a subsidy if they would switch over.

There is urgency to perform this outreach quickly given that the ARP makes PTC expansion effective for 2021 (and also increases CSRs for certain individuals in 2021 only). These expanded benefits are available only for months of Marketplace enrollment, so each month eligible for them but uninsured—or off-Marketplace—is a month forgoing the expanded subsidies. Current Marketplaces enrollees may also benefit from returning to the Marketplace to receive additional subsidies or a plan that better fits the consumer’s needs given increased subsidies. This urgency will extend to 2022 coverage, and may be further heightened when the public health emergency expires, ending Medicaid eligibility for consumers who may then be PTC-eligible.

The role of reinsurance programs becomes uncertain, suggesting caution in immediate decision-making. Reinsurance programs are a key success story in recent state health policy. Fifteen states of every political stripe have received federal Section 1332 state innovation waivers to help fund reinsurance programs, which reimburse insurers for a portion of the costs associated with high-cost enrollees and thereby reduce the list premiums paid by unsubsidized individuals. By reducing the number of unsubsidized individuals and also reducing net premiums broadly, the ARP suggests a reexamination of the role of reinsurance. At the same time, uncertainty and the costs of changing course caution against any sudden shifts.

If the ARP’s PTC expansion were made permanent, the case for ongoing, broad-based reinsurance programs would be less clear, for several reasons. Reinsurance waivers were devised after states like Alaska and Minnesota saw huge premium increases when federal stabilization programs expired after 2016, substantially increasing costs for unsubsidized consumers. The PTC expansion generally addresses this concern about unbounded consumer costs by broadly capping premium contributions at no more than 8.5 percent of income. The PTC expansion also shifts the benefit of reinsurance up the income scale. Reinsurance primarily helps unsubsidized consumers, since others are generally insulated from premium changes by the PTC. Expanding PTC narrows this unsubsidized group to a smaller group of generally higher-income individuals.[6] It also increases the number of consumers receiving PTC, which may exacerbate concerns about reinsurance waivers sometimes reducing purchasing power among PTC recipients. And in the long run, expanded PTC will itself reduce list premiums by attracting healthier consumers. The Urban Institute estimates that over time a PTC expansion like the one in the ARP would reduce list premiums by 15 percent. Strengthening the risk pool in this way could mitigate the need for broad-based reinsurance programs.

That said, PTC expansion will also likely reduce the costs states incur to operate reinsurance programs. With more people getting PTC, states should receive more federal pass-through funding to operate their reinsurance programs. How much is unclear—the Biden Administration has not updated its initial calculations of 2021 pass-through amounts or Treasury Department guidance on the calculation since the ARP passed.

Uncertainty about the PTC expansion beyond 2022 also complicates state decision-making. Since it is likely too late to change course for 2021, states are effectively looking at only one future year (2022) when expanded PTC clouds the case for reinsurance.[7] Applying for a waiver requires a significant investment of time and resources. Given the risk that the PTC expansion will expire, it seems premature to make a change that requires a new application.

Taken together, these considerations caution against making lasting changes until matters are clearer. Instead, states considering changes may wish to focus for now on 2022, while keeping options open for 2023 and beyond.

States that wish to modify their reinsurance programs for 2022 may have several options. There may be flexibility under state legislation and waiver terms to substantially reduce the size and cost of 2022 reinsurance programs, thereby reserving resources for other purposes in 2022 or later years. A reinsurance program might also be modified to achieve complementary goals. For example, it could be targeted to reduce premiums in geographic areas with limited competition, with differential parameters like the ones in effect today in Colorado. Or it could potentially be modified to help address the challenges of setting 2022 rates in the face of recent policy changes and pandemic-related disruptions. One way to do that might be to provide greater assistance to plans that are ultimately less profitable, offering a buffer similar to the ACA’s risk corridor program. For this last approach, a key question will be whether it reduces premiums (and therefore generates pass-through funding) as efficiently as a traditional reinsurance.

For any of these options, the details would need to be locked down quickly to take effect for 2022. But if they could be worked out, options like these could maximize the benefit of reinsurance programs for 2022 while preserving options for 2023 and beyond.

Other measures to reduce list premiums may be valuable for reasons other than increasing consumer affordability. As with reinsurance, PTC expansion may change the calculus for other state measures aimed at lowering individual market list premiums. Such measures include the aggressive use of rate review, provider payment reforms, and some approaches to public options.

While it is in effect, PTC expansion may dampen the urgency of reducing list premiums to make coverage affordable for consumers. It also reduces the extent to which premium reductions translate into direct savings for consumers.

That said, PTC expansion may not weaken other reasons to pursue these options.

For example, PTC expansion leaves in place—and even strengthens—another key reason to reduce list premiums in the individual market: drawing down federal funding under a Section 1332 waiver. Under Section 1332, states can receive pass-through funds to the extent they create federal savings, generally by reducing list premiums and thus PTC expenditures. While only reinsurance has been used in this way to date, other approaches to reducing premiums might also be compatible with a Section 1332 waiver. And for a given measure that reduces premiums, the PTC expansion should increase the federal savings generated and thus the funding for states.[8] Those pass-through funds could, in turn, be used to support the types of state subsidy programs described above, or other measures to support coverage.

States may also have other motivations for pursuing policies that would have the effect of reducing list premiums. For example, states may view a public option as a tool for providing more generous benefits, ensuring adequate consumer choice, promoting health equity, or reducing the role of for-profit companies in the health care sector.

In short, to the extent the goal of these measures was to reduce the premiums paid by consumers, they seem less important with the expanded PTC. But to the extent states were considering them for other policy reasons, they may still make sense, and may even be more valuable.

Finally, regardless of how permanent expansion might alter states’ thinking about the policies, as with reinsurance, ongoing uncertainty cautions against quickly changing direction or abandoning areas of policy exploration. Instead, states may wish to use the time afforded by the ARP to explore a range of options, including those consistent with the PTC expansion expiring or being extended.

Measures that improve plan generosity—but may marginally increase premiums—become more attractive. States have tools besides cost-sharing subsidies to increase the generosity of individual market coverage. These include selecting a more generous essential health benefit (EHB) benchmark, strengthening network adequacy requirements, using active purchasing authority to keep out lower-quality plans, and using standardized plan authority to require silver plans to have an actuarial value of 72 percent (the top of the “de minimis” range permitted by CMS regulations).

These policies have historically presented states with a trade-off: they make coverage more generous but may increase list premiums and so increase costs for unsubsidized consumers. With the expanded PTC making almost all individual market enrollees eligible for subsidized coverage, these options become more attractive. Similar logic applies to measures requiring issuers to price silver plans to fully account for the cost of silver CSR variants.

Options of this sort may be especially attractive with the current uncertainty given that they generally require less start-up cost than subsidies or waivers and may be feasible without additional state legislation. That said, it may be too late to implement some or all of these options for 2022, but they may be worth considering for 2023 and later years in the event the PTC expansion is extended.

Section 1332 waivers and BHPs may provide new opportunities but require thoughtful consideration. Section 1332 waivers and BHPs both allow states to receive federal funding to support state programs in return for reducing federal PTC spending. Under Section 1332, states can receive pass-through funding in the amount of federal PTC savings created by the waiver. Under BHPs, states cover people with incomes up to 200 percent of FPL in a state-run plan and receive federal funding equal to 95 percent of the PTC these people would have received. In both cases, PTC expansion could make these options more useful by lifting the ceiling on the potential funding states might receive to operate the program. At the same time, PTC expansion raises the standards these programs must meet and may have additional effects for states to consider.

As discussed above, PTC expansion creates the potential for more pass-through funding under Section 1332 waivers. Provisions that reduce list premiums (public options, payment reforms, etc.) should generally draw down more pass-through funding given higher baseline PTC spending. PTC expansion may also increase the feasibility of broad waivers that replace the PTC with state-based subsidies, since less state funding will be needed to make a state subsidy sufficiently generous to make such a change seem worthwhile. On the other hand, PTC expansion will also increase the baselines of coverage, affordability, and comprehensiveness that waivers must sustain to be approved, which could pose a challenge for some waivers.

For BHP, the impact of PTC expansion may be even harder to predict, or at least to generalize. BHP funding for each covered individual should increase since it is tied to the PTC. This increased funding will be offset to some extent by the requirement that BHP coverage be no less affordable than the subsidized Marketplace coverage the individual could otherwise receive—a standard that is now higher. That said, federal funding for the BHP program in New York has to date generally been sufficient to exceed these affordability requirements. To the extent other BHPs could also provide affordability at lower cost than Marketplace coverage—perhaps through savings on provider reimbursement rates, administrative costs, or issuer profits—PTC expansion could provide a greater BHP surplus that could be used for further improvements. Another consideration is that BHPs diminishes the benefit of silver loading by diverting consumers otherwise eligible for high-value CSRs. PTC expansion may magnify this effect by extending the PTC—and thus the benefit of silver loading—to many additional consumers who would not be BHP-eligible.[9] Given these countervailing considerations, states considering this path should undertake careful analysis.

Ongoing uncertainty requires a thoughtful approach to Section 1332 waivers and BHPs. Both programs require detailed planning, the solicitation of public comment, a complex application progress, and often-intensive implementation. States already strongly considering one of these options for 2022 and ready to apply quickly may be able to take advantage of elevated funding, while keeping in mind that future subsidy enhancements are not guaranteed. States that are further behind in the process may need to forgo 2022 PTC enhancements and move forward with developing options while retaining flexibility to respond to changes in the federal landscape.

Interactions with employer coverage. Some states have explored measures to encourage employer-provided health coverage, for example by supporting the small group market or encouraging the adoption of account-based health benefits like health reimbursement arrangements (HRAs). The PTC expansion may change the calculus for these measures by making the benefit of employer coverage smaller on average relative to the benefit of receiving the PTC.

It has long been the case that some consumers—especially those with lower incomes—are worse off with an employer offer than they would be if they could receive the PTC. The best-known example of this is the so-called “family glitch,” which may deny the PTC to an entire family when employer coverage for the family would consume a large fraction of income. But it has also been true in other cases, since an employer offer requiring the employee to pay nearly 10 percent of income (9.83 percent in 2021) prevents an employee from receiving a PTC that at lower incomes requires a far smaller individual contribution. For employers deciding whether to offer coverage, this dynamic has been balanced by incentives on the other side, including the long-standing tax exclusion (which is quite valuable at higher incomes), the employer mandate, and in some cases employee preferences.

The ARP shifts this balance by increasing the size of the PTC and the number of people potentially eligible. It also leaves the affordability standard at 9.83 percent even as it reduces the applicable percentages, thereby increasing the potential disparity between the generosity of PTC and employer coverage. For example, a consumer with income at 150 percent of FPL (around $40,000 for a family of four) is now generally eligible for PTC that fully covers the cost of highly generous (94 percent AV) coverage. But such an individual would be ineligible for the PTC if offered employer coverage costing up to 9.83 percent of income—or a much larger amount for family coverage. In short, the ARP shifts the balance towards employees being better off without an ESI offer.

If the PTC expansion were made permanent, this shift could have a meaningful impact on employer behavior—especially for small employers exempt from the ACA’s employer mandate, who would pay no penalty for dropping their health plans. If PTC expansion expires after 2022, the impact on employer behavior would be greatly attenuated. Nonetheless, states may want to consider these dynamics in exploring policies that could impact employer decisions in 2022 or thereafter.

Conclusion

The ARP’s broad-based PTC expansion offers great promise to improve health coverage and build on the ACA. It immediately alters considerations for states’ options to invest in their markets, and if extended may support innovations that are otherwise out of reach. While the uncertainty around the PTC expansion adds a level of complexity to state decision-making, remaining flexible in policy and implementation decisions can help state coverage programs create significantly more affordability and accessibility.

The authors did not receive financial support from any firm or person for this article or from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this article. They are currently not an officer, director, or board member of any organization with an interest in this article.

[1] The ARP also makes other changes related to private health coverage, including forgiving repayment of excess advance PTC payments (APTC) for tax year 2020, providing a temporary COBRA subsidy for April through September of 2021, and providing highly generous PTC and cost-sharing reductions in 2021 for individuals receiving unemployment compensation. Since these measures all expire by the end of 2021, they are less relevant to state decision-making going forward and are not generally addressed in this piece. The legislation also makes changes to the Medicaid program that are also beyond the scope of this piece.

[2] As noted in an earlier footnote, the ARP expands cost-sharing reductions only for individuals receiving or found eligible for unemployment compensation, and only in 2021.

[3] See, for example, ongoing work in Washington, Maryland, and Connecticut.

[4] The only partial exception to this is Massachusetts, where at low incomes the combined pre-ARP premium subsidies are about as generous as the ARP’s expanded PTC. The Massachusetts subsidies extends to 300 percent of FPL, so beyond that level the expanded PTC is more generous.

[5] Colin Baillio, “What do the American Rescue Plan’s enhanced subsidies mean for Native Americans?” Presentation to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners, March 2021. On file with author.

[6] As noted above, lower-income consumers may also be unsubsidized due to the family glitch or for other reasons. These groups may be more efficiently helped through a targeted subsidy or other means than by lowering list premiums for everyone.

[7] It is likely too late to turn off reinsurance programs for 2021, in part because premiums were developed in reliance on them.

[8] Additional considerations for Section 1332 waivers are discussed below.

[9] The BHP payment methodology includes an adjustment factor to account for the impact of CSRs. But the PTC in BHP states is still based on the second-lowest-cost silver plan premium in the state, which is not adjusted to account for the forgone CSRs.